Today Heterodox at USC brings you an opinion piece from group member Anna Krylov. We welcome feedback and responses to this piece via email at heterodox.usc@gmail.com.

In his memo of 01/15/2025, Provost Guzman announced the creation of the Provost-Senate Joint Task Force on Academic Freedom and Professional Responsibility. The task force, co-chaired by John Matsusaka (Marshall School of Business) and Robert Rasmussen (Gould School of Law), will investigate the state of academic freedom and professional responsibility, and develop recommendations on policy and implementation (see here for Heterodox at USC newsletter announcing the task force).

I was delighted by this development and honored to be invited to serve on the task force. In what follows, I share my personal views on free speech and academic freedom and offer some thoughts on the challenges we face at USC.

The announcement came on the heels of an electrifying three-day conference, Censorship in the Sciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, which featured presentations from nationally and indeed internationally recognized champions of free speech and academic freedom.

The focus of the conference was on censorship of scholarship and research in the sciences (both STEMM and the social sciences). The broader topics of academic freedom and free speech on campus were, however, also discussed.

In a plenary talk, the president of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), Greg Lukianoff, outlined the perilous state of free speech on American campuses and (inadvertently) reminded us of USC’s abysmally bad score on FIRE’s rating of campus free speech — USC was rated the seventh worst school in the entire country.

The creation of the task force is timely and much needed. I consider its formation to be a sign of institutional willingness to change course towards improved polices and culture.

Why academic freedom is important

The memo states: “Academic freedom, free expression, and open discourse are among USC’s core values and essential to advancing the university’s educational and research missions.” To put this in context, the mission—the telos—of a university is truth seeking. Hence, any interference with the free and unfettered pursuit of truth—in classrooms, research labs, scholarly communication, or communication in the public square—undermines this mission.

As pointed out by many brilliant thinkers, starting with John Stuart Mill, suppression of any idea—whether good or bad, correct or mistaken, virtuous or evil—hinders our ability to find the truth. Open airing of opinions and uncensored debates enable good ideas to gain hold, bad ideas to be debunked, and imperfect ideas to be improved. This argument is known as Mill’s trident, which holds that, for any given belief, there are three options:

You are wrong, in which case freedom of speech is essential to allow people to correct you.

You are partially correct, in which case you need free speech and contrary viewpoints to help you get a more precise understanding of what the truth really is.

You are 100% correct. In this unlikely event, you still need people to argue with you, to try to contradict you, and to try to prove you wrong. Why? Because if you never have to defend your points of view, there is a very good chance you don’t really understand them, and that you hold them the same way you would hold a prejudice or superstition. It’s only through arguing with contrary viewpoints that you come to understand why what you believe is true.

[Lukianoff, Mill’s (invincible) Trident: An argument every fan (or opponent) of free speech must know, FIRE]

Mill’s trident holds true in the classroom, in the research lab, and in scientific communication. In these contexts, the free exchange of ideas and uncensored debate is known as academic freedom. Academic freedom is instrumental for the pursuit of truth; undermining it prevents scientists from producing knowledge, does a disservice to students, and ultimately harms society at large.

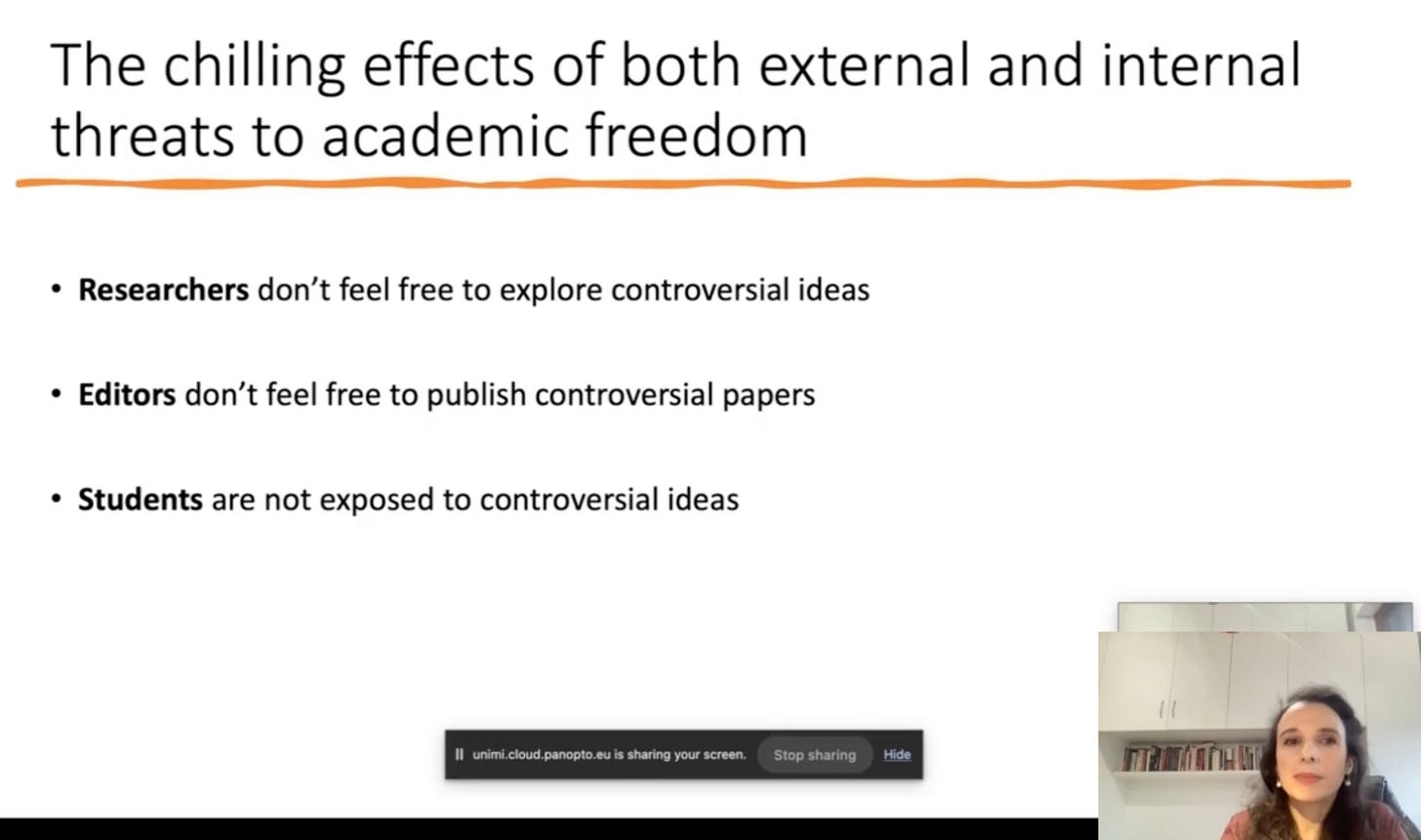

Francesca Minerva, co-editor of the Journal of Controversial Ideas, eloquently explained why we care about academic freedom in her address to our conference:

When academic freedom is under threat, we end up hindering the pursuit of truth…. We end up with the distortion of the nature of academia.… And when we do not pursue the truth...we end up failing students.… We also fail society at large because non-academics have an interest in benefiting in what academic have discovered when they do their job properly and without restriction.

Thus, academic freedom is essential for science to operate, for students to be educated, and for society to prosper and function.

The concept of Academic Freedom has a long and complicated history. A book by the Yale constitutional scholar Keith Whittington provides an illuminating account of the evolution of academic freedom in the U.S. and its intricate relationship with the First Amendment.

By reviewing milestone court cases, Whittington explains the domains covered by academic freedom, its limits, its application to government or private employees, and its interplay with professional duties and responsibilities. He also provides illuminating analysis of recent legislative attempts, such as in certain provisions of the Stop the Woke Act in Florida, to restrict the ideas discussed on university campuses, and argues that existing constitutional doctrine can be effectively deployed to protect free inquiry. The book is written in a clear manner, accessible to scholars in all fields, including STEMM. It should be required reading for any academic freedom committee.

My position on academic freedom

As someone who grew up under a totalitarian regime, I am alert to the telltale signs of illiberal tendencies, even when they disguise themselves with Orwellian language. In this interview with the Academic Freedom Alliance, I described how I became concerned about free speech and academic freedom in America:

I grew up in Soviet Russia. There, I was acutely aware of the absence of freedom of speech—that was one of the defining aspects of our reality. You could not express your opinion, you could not ask questions, many topics were taboo, and thoughtcrime was very real.

In 1991, the regime collapsed and I moved to Israel and then to America. Living in democratic countries, I largely stopped thinking about freedom of speech. To give you an analogy, when you are healthy, you do not think about how exactly your body is functioning. You do not think about how it executes its motions—you wake up, roll out of bed, and do your chores without much thought. But if you, say, twist your knee or break your arm, then you suddenly become very aware of what needs to be done for each particular task. You suddenly understand that, in order to tie your shoes, your knee needs to bend, your wrist needs to twist, and so on—you are made acutely aware of the structure and the mechanics of your body and especially about the parts that are injured.

Freedom of speech is similar. When it’s there, in a healthy society, you do not think much about it—you just carry on with your life. But when our essential institutions are broken and things are not working properly, as I think is happening in our country now, you become acutely aware that something’s wrong. You cannot fulfill certain functions, just as if you had a broken arm or twisted knee.

I became aware of freedom of speech and academic freedom again a couple of years ago when I started to notice alarming trends in the scientific community and in society in general.

Academic freedom, of course, is more than just free speech. Free speech—the freedom to ask questions and to communicate one’s ideas—is a prerequisite, but academic freedom also entails the freedom to pursue research—asking certain questions about the inner workings of the world, interrogating them in the lab, and communicating the answers that emerge, regardless of whether we like them or not.

This is why I became a founding member of the Academic Freedom Alliance (AFA), an organization launched in 2021 to defend academic freedom. (For a brief overview, listen to my 10-min presentation at the censorship conference, Day 2 recording, starting at 2:07:09 and a 4-min blitz talk by AFA director Howard Muncy, Day 3 recording, starting at 2:59:09.) I currently serve on the organization’s Academic Committee.

My take on academic freedom at USC

There are good reasons that USC scored so badly in FIRE’s free speech rankings, and I am not going to belabor them here. Instead, I want to briefly summarize where I see opportunities for improvement.

Policies and their enforcement

The gold standard of academic freedom policy is the Chicago Trifecta: the Chicago Free Speech Principles, the Kalven Report, and the Shils Report. I concur with University of Chicago geo-scientist Dorian Abbot, who wrote:

All universities should adopt and enforce rules requiring that: (1) the university, and any unit of it, cannot take collective positions on social and political issues; (2) faculty hiring and promotion be done solely on the basis of research and teaching merit, with nothing else taken into consideration; and (3) free expression be guaranteed on campus, even if someone claims to be offended, hurt or harmed by it. Faculty need to work together with students, alumni, journalists and politicians to get this done.

Although USC has not adopted the Trifecta, we have similar-in-spirit policies, as outlined in the USC Policy on Free Speech (analogous to the Chicago Principles), which states

All members of the university community have a responsibility to provide and maintain an atmosphere of free inquiry and expression respecting the fundamental human rights of others, the rights of others based upon the nature of the educational process and the rights of the institution.

USC also has a policy on institutional neutrality, a (regrettably) somewhat weaker analogue of the Kalven Report, which prohibits departments from making political statements on behalf of their constituents. A 2024 memo from the President concisely summarizes these and other relevant policies (such as rules about time, place, and manner governing protests and demonstrations).

Overall, although USC policies may be not up to the gold standard, they provide a sound foundation for supporting free speech and academic freedom. The real problems are how these policies are implemented in practice, their respective enforcement mechanisms, and the poor state of our campus’s free speech culture. Below, I outline these problems.

Problem 1: The weaponization of Title IX and Title VI

Our university lacks robust protection for faculty and students from frivolous Title IX and Title VI complaints. We need effective mechanisms to prevent bad-faith actors from weaponizing Title IX, Title VI, and other anti-harassment policies. As far as I know, there is no punishment for making false accusations, and such accusations can trigger lengthy and painful internal investigations, which are a form of punishment themselves and have a chilling effect on free speech. Two recent examples illustrate this problem:

Greg Patton, a USC communication professor, was suspended and publicly chastised in a statement by the dean for using a harmless Chinese word to illustrate a concept in class. The incident, which was widely publicized (resulting in USC becoming a laughingstock) is described here and here. No public apologies to Professor Patton were ever issued, and the students who lodged the ridiculous complaint against him were not disciplined.

John Strauss, a professor of economics, was removed from campus and subjected to lengthy investigations for voicing his opinion about Hamas in a verbal exchange with pro-Palestinian protesters.

Both examples were clearcut expressions of protected speech according to existing USC policies, and the complaints should have been dismissed immediately.

This issue is not limited to USC. One of the urgent recommendations that Greg Lukianoff made to the President of the United States was to “address the abuse of campus anti-harassment policies that erode free speech.”

Problem 2: Lack of enforcement of university policies

Academic units at USC frequently violate university policy on neutrality. For example, during Spring 2024, many departments and academic units issued charged political statements and manifestos, published on university letterhead and often formulated on behalf of the entire unit (for examples, see here). There have been no publicly visible actions or statements against these violations.

Problem 3: Academic freedom has its bounds, and these bounds need to be respected

According to Whittington:

Traditional principles of academic freedom are understood to be qualified, not absolute. In the particular context of classroom speech, faculty speech is delimited by requirements of germaneness and professional competence.

Academic freedom does not protect academic hooliganism, such as replacing final exams by participation in political rallies or hijacking classrooms for blatant propaganda (some examples of this at USC and other universities can be found here and here). Such unprofessional actions by faculty undermine the learning process and create a hostile environment, thus violating students’ rights to receive the education they were promised. To protect its educational mission, the university must both protect the academic freedom to discuss controversial concepts in a classroom and maintain high standards of our curricula.

We need a culture of academic freedom

While policies and mechanisms for their enforcement are essential for protecting free speech and academic freedom, they alone are not sufficient. We need to cultivate a climate of free speech on campus and educate our community about it. Based on my interactions with students and faculty, the level of understanding of the First Amendment and the very concepts of free speech and academic freedom is abysmally low.

This is in part due to the lack of civic education, and in part due to the preponderance of cancel culture and the victimhood and harms mentality promulgated by the D.E.I. bureaucracy. Even worse, is the lack of appreciation of the effect of suppressing the free exchange of ideas on the university’s educational and research missions. This gap needs to be filled—by education, not by mandatory trainings.

The current USC Student Handbook contains an overview of the university’s free speech policies, including clear explanations of the boundaries of free expression (including time, place, and manner regulations) and explanations of the university’s right to regulate certain speech.

The Handbook also states: “All students, both undergraduate and graduate, are required to complete a series of online training courses upon enrollment and periodically thereafter. Failure to complete any required course may result in a hold that could prevent students from registering for the subsequent semester, or other administrative action. More information about completing these trainings is available at each student’s myUSC.”

This is exactly the wrong way to approach the problem. As I wrote here:

This is, unfortunately, the route that many universities have chosen. Why do students need these trainings? Should students not be treated as adults? The rules are listed in the Handbook and it is students’ responsibility to learn them. Then, if they violate them they will face consequences. A few expulsions would be much more effective in driving home the message than a series of mandatory trainings. Being coercive, these trainings cause justified resentment, inducing opposition to the very ideas they purport to instill. Moreover, training is not education. We train our pets. We educate—hopefully—our students. Rather than compel trainings, wouldn’t it more effective to offer free speech seminars centered around one of the many excellent books on the subject (see, for example, Greg Lukianoff’s list “Required Reading for ‘Free Speech 101’”) and events featuring inspirational speakers—such as Jonathan Haidt, Gad Saad, Nadine Strossen, Greg Lukianoff, to name a few.

To create a free speech climate on our campus, we should provide intellectually substantive and engaging programming, such as our conference Censorship in the Sciences: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Such scholarly events will raise awareness of free speech issues, pique students’ interest in civic discourse, and educate the USC community in these important matters.

I am looking forward to working with my fellow task force members to tackle these challenges. I hope that together we help USC be more faithful to its mission and make our university a better place to work and study.

More about the task force

Task Force Chairs

John Matsusaka (Marshall School of Business) and Robert Rasmussen (Gould School of Law)

Task Force Members:

Hossein Hashem; Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering (Viterbi School of Engineering)

Velina Hasu-Houston; Distinguished Professor of Theatre in Dramatic Writing (School of Dramatic Arts)

Anna Krylov; USC Associates Chair in Natural Science and Professor of Chemistry (Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences)

Morris Levy; Associate Professor of Political Science and International Relations (Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences)

Etan Orgel; Professor of Clinical Pediatrics (Keck School of Medicine)

Dan Pecchenino; Professor (Teaching) of Writing and former President of the Academic Senate (Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences)

Neeraj Sood; Professor of Public Policy (Price School of Public Policy)

Miki Turner; Professor of Professional Practice of Journalism (Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism)

Task Force Advisory Members:

Andrew Guzman; Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs

Beong-Soo Kim; Senior Vice President and General Counsel

Marty Levine; Vice Provost and Senior Advisor to the Provost; UPS Foundation Chair in Law and Gerontology, and Professor of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Science (Gould School of Law)

References

Dorian Abbot, Chicago Trifecta, European Review v. 31 p. 556 (2023)Anna Krylov, Censorship Undermines the Pursuit of Truth, HxSTEM, 2025

Anna Krylov, The Peril of Politicizing Science, J. Chem. Phys. Lett. v. 12 p. 5371, 2021

The Science of Freedom: a Conversation with Anna Krylov, Academic Freedom Alliance, 2022

Greg Lukianoff, Answers to 12 Bad Anti-Free Speech Arguments, Quillette, 2024

Greg Lukianoff, How Cancel Culture Destroys Trust in Expertise, YouTube

Greg Lukianoff, My Letter to the Incoming President, The Eternally Radical Idea, 2025

Greg Lukianoff, Mill’s (Invincible) Trident: An Argument Every Fan (or Opponent) of Free Speech Must Know

Robby Soave, USC Suspended a Communications Professor for Saying a Chinese Word that Sounds Like a Racial Slur; Reason, 2020

Eugene Volokh, USC Communications Professor “on a Short-Term Break” for Giving Chinese Word “Neige” as Example; The Volokh Conspiracy, Reason, 2020

Keith Wittington, You Can't Teach That: The Battle over University Classrooms

Heterodox Academy YouTube channel: USC Censorship in the Sciences playlist

Additional resources (including links to Student and Faculty handbooks) USC: Freedom of Expression

Note: Views expressed in this essay are my own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the institutions and organizations I am part of.

Thank you Anna. Perfect reading to prepare for the first meeting of the task force.

"This is, unfortunately, the route that many universities have chosen. Why do students need these trainings? Should students not be treated as adults? The rules are listed in the Handbook and it is students’ responsibility to learn them. Then, if they violate them they will face consequences. A few expulsions would be much more effective in driving home the message than a series of mandatory trainings. Being coercive, these trainings cause justified resentment, inducing opposition to the very ideas they purport to instill. Moreover, training is not education. We train our pets. We educate—hopefully—our students. Rather than compel trainings, wouldn’t it more effective to offer free speech seminars centered around one of the many excellent books on the subject (see, for example, Greg Lukianoff’s list “Required Reading for ‘Free Speech 101’”) and events featuring inspirational speakers—such as Jonathan Haidt, Gad Saad, Nadine Strossen, Greg Lukianoff, to name a few."

Bingo.

Along with the rest of your article.

Thank you!